China may not be a dependable ally for Bharat. Reconciliation and reset noises made by President Xi’s hawks could be tactical and unsustainable.

Dr Amritpal Kaur

Is China a dependable ally for Bharat? Or, is it safe to play a balancing act between China under President Xi Jingping and US where Donald Trump is expected to take charge as President beginning 2025?

Both Beijing and Washington DC pose different sets of challenges given Bharat’s 75-years’ experience post-independence from British imperialistic rule.

At a time when there has been huge debate on ‘strategic autonomy’ as an instrument of Bharat’s state policy, there have been key developments ranging from threats hurled by US President-designate Donald Trump on tariffs regime to Beijing moving to purportedly normalize relations with Bharat.

Undertones of the incoming Republican regime and firmly trenched third-term Chinese Communist Party regimes are different.

At a time when strategists in New Delhi were breathing easy at lasting solution to clashes on Eastern Ladakh front, China opened a new front on Dokolam front with contours of its expansionist face coming to the fore.

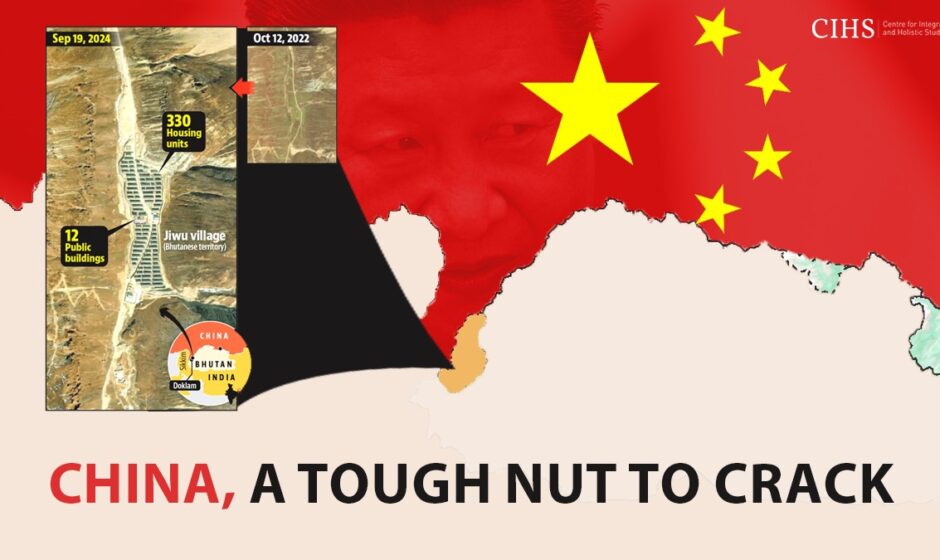

Reportedly, China encroached into Bhutanese territory, crossed the buffer zone and put up as many as 22 villages in last eight years. Drone images of these villages constructed on Bhutanese territory and splashed on front pages of major Bharat newspapers reflected on the intent of Chinese communist party regime. Parceling away pieces of neighbours’ territory and encroachment by design has been well rehearsed strategy of dragon regime.

These images apart from US closing-in that China has never backed out from both Ladakh and Dokolam front came at a time when Bharat’s national security advisor Ajit Doval was in Beijing to attempt ‘normalizing’ relations with President Xi’s hardnosed negotiators.

Ramifications of Chinese incursions into Bhutanese territory have strategic and regional security implications. China’s deliberate efforts to alter ground realities and impose a fait accompli are seen in construction of settlements on the Doklam plateau, a region vital to India’s Siliguri Corridor.

In violation of 1998 China-Bhutan agreement which explicitly calls for maintaining status quo and refraining from unilaterally altering borders, this makes an absurdity of China’s claims and evasive justifications for the acts.

These advances are a flagrant imitation of China’s use of armed force to occupy South China Sea in order to evade its duties under international law and further its expansionist objectives.

It’s in this backdrop that cautious attempts made to resolve broader Bharat -China ties have taken place. On October 21, 2024 on sidelines of BRICS summit in Kazan Russia, Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri announced that India and China had reached a patrolling agreement on the Line of Actual Control leading to disengagement in areas where issues had arisen in 2020.

This announcement paved way for a brief meeting between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi Jinping on sidelines of BRICS summit, a first in about five years since Galwan clashes of 2020. On November 19, Bharat’s Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar met his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi on sidelines of G-20 Summit in Rio De Janeiro. He was matter of fact and reiterated that disengagement at two contentious points on Indo-Chinese Border is a ‘welcome step’. There is a long way to go in Indo-China relations and it’s a fact.

A day after, on November 20, Defense Minister Rajnath Singh met his Chinese counterpart Admiral Dong Jun on sidelines of Asean Defense Ministers’ Meeting Plus in Vientiane, Laos where he too stressed on need to maintain harmonious relations between the two Asian neighbors.

Flurry of meetings indicate possible rapprochement between India and China according to optimists. But, caution is imperative given history of the two Asian giants coupled with present day real politic. It is hard to miss conspicuous concoction of events and processes happening around which have forced Chinese to even concede that border disengagement was going on, something to their eyes a tactical compromise giving away the psychological advantage to Bharat.

Given that Chinese rarely give away the territory they captured after ‘salami-slicing’ the pressure must have been great for Beijing to engage with India in a positive way. The question it begs is, what exactly changed for the Chinese in past two years that from showing off the Commander of Galwan clash as the hero in the National Assembly, which crowned President Xi with unprecedented third term, to a visible attempt at bonhomie with India?

It is significant to look beyond South Asia to recent happenings in the world. To begin with, United States elected Donald Trump as its new President. If previous Trump administration is guide to his second term outlook, Chinese have a reason to brace themselves for the ride.

Coupled with military maneuvering of PLA in Taiwan Strait to indicate the tensions between China and Taiwan, it makes sense for them to not open another front with India, so that focus remains on its southeast border.

Secondly, Chinese ally Russia is fighting war in Europe for more than two years now and another ally Iran is engaged in West Asian conflict with Israel which has potential to spill out into the larger region war creating stress on the Sea lanes of trade and communication, something crucial for China.

In strategic parlance, it makes sense to not open another theater of conflict or at least keep other areas peaceful should the push comes to shove, but the sensible would see the game and ask whether underlying structural problems in Indo-Chinese relations have been resolved before we declare the ‘reset’ of ties.

If History is the guide to Indo-China relations, beyond early days of Nehru era, relations between the two were never ‘friendly’. Chinese internal conversations show that even then India was seen as stooge of Imperial Britain and Liberal democracy which is diagonally opposite Communist China.

The era of reforms and globalization had given hope to believe that thriving trade and commerce would act as a credible deterrence against any hostilities, but even here the unhealthy trade deficit between the two countries only prove that the relationship has been abysmally one dimensional.

It’s advisable to see how Chinese trade policy has fared for the other third world nations like Sri Lanka and Maldives to analyze the possible impact of Chinese investments into Indian markets. It is one thing to desire foreign direct investments and it is a whole new ball game to desire investments from a neighbour like China with history of weaponizing trade and investments in the most glaring terms.

Also, how China – Pakistan ‘all-weather’ friendship created the arc of strategic uncertainties for India, with a reticent Nepal in the mix only goes on to prove that given the situation, there are few bargaining chips in Indian hands and to believe that friendship between India and China can be democratic and equal is a misunderstanding in best of circumstances.

What it does means however is that there is a need to manage relations with all neighbours including China as they are a permanent fixature for any foreign policy framework.

Given that China will be embroiled with Taiwanese issue in near future, central plank of CCP and President Xi, Beijing would bet big time on it. Situation for them can be greatly exacerbated by second Trump administration and its own relations with Taiwan. East Asia is not looking particularly amiable for Chinese adventure given shift in the Japanese post second world war security policy.

It should be crystal clear to us that Chinese overtures are contingent upon their own peculiar situation at this moment and not particularly to the reason that Indian friendship has become pertinent to them.

Hence, present rapprochement is highly unlikely and what we are witnessing is a tactical retreat to status quo ante. Normalcy in Indo-Chinese relations is an uphill task fraught with Beijing’s unilateral selfish interests which seek to defy norms governing sovereign nations. Till these one-sided notions are not addressed and ameliorate, ‘reset’ of Indo-Chinese relations will remain a distant dream.

(Author is Assistant Professor in Political Sciences, Dayal Singh College, Delhi University, New Delhi)