As the UK continues to grapple with the complex intersection of Islamophobia, grooming gangs, and free speech, it must also decide if it is ready to confront all forms of religious intolerance including Hinduphobia with equal urgency.

Rahul PAWA

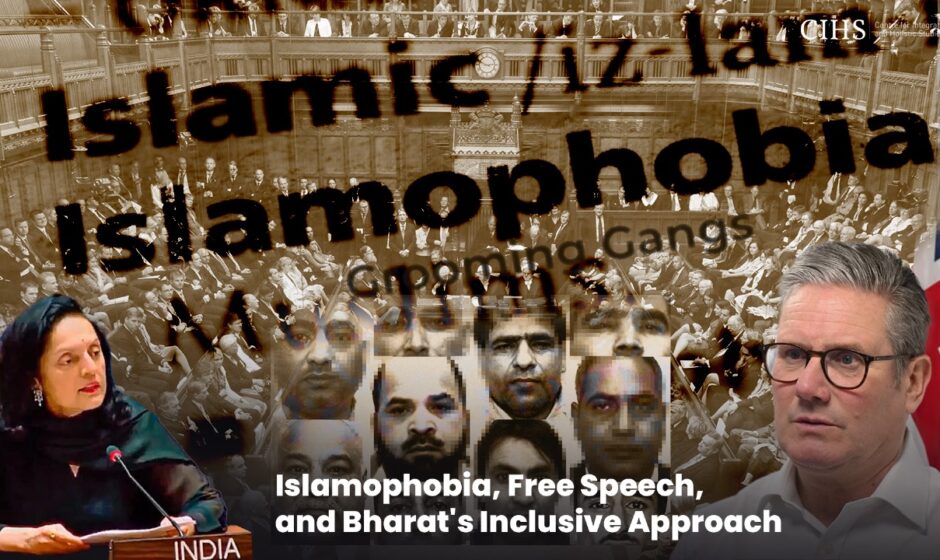

In recent political discourse, the question of how to define and tackle Islamophobia has gained increasing prominence in the UK. The Labour Party, led by Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner, is currently considering the adoption of a formal definition of Islamophobia. While some support this move, arguing it is crucial to safeguard Muslim communities, others raise concerns about its potential consequences—particularly for free speech. These critics warn that such a definition, much like the one introduced for anti-Semitism in 2016 under Theresa May’s government, could ultimately be used to suppress critical discussion of Islam.

The term “Islamophobia” itself is still under intense scrutiny. Defined by the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on British Muslims in 2018 as a form of racism targeting expressions of “Muslimness or perceived Muslimness,” it has been applied to a wide range of events and behaviors. However, the ambiguity of this definition—along with its evolving use—raises critical questions. Is Islamophobia truly a “phobia,” a fear of the religion or its adherents, or is it a term that encompasses prejudice and cultural conflicts that extend beyond mere fear?

This issue has come to the forefront at a particularly delicate time in the UK, as broader social issues surrounding cultural and religious tensions also take center stage. For instance, the rise of discussions about the country’s grooming gang scandals—particularly in Rotherham, Rochdale, and Oxford—has created a political and social backdrop that adds complexity to the Islamophobia debate. The grooming gang issue in the UK, which involved men of Pakistani Muslim exploiting young girls, has raised uncomfortable questions about how communities of different faiths and cultures integrate into British society. The gangs operated across multiple towns, with the Rotherham case alone documenting over 1,400 girls who were victims of systematic abuse spanning 16 years. Public inquiries like the Jay Report and Operation Stovewood have exposed deep institutional failures to address the scale of the abuse, with accusations that political correctness and fear of being labeled racist or Islamophobic allowed the issue to fester unchallenged.

The cultural aspect of these crimes—many of the perpetrators being from Muslim backgrounds—has been largely avoided in public discourse. Politicians, law enforcement officials, and even journalists have often been reluctant to address the role that certain cultural practices and religious ideologies may play in such crimes, due to the fear of being accused of Islamophobia. The reluctance to openly discuss the perpetrators backgrounds adds another layer of difficulty to the issue, as it becomes wrapped up in the broader question of how to engage with a community that feels increasingly marginalised yet protected by a label as politically charged as “Islamophobia.”

In this environment, debate over defining Islamophobia becomes especially crucial. Critics of a formal definition argue that such a measure could turn into a legal or cultural “blasphemy law,” limiting the ability to critique Islam, its teachings, and its influence on certain practices—especially in the case of controversial issues like the grooming gang scandal.

The term “Islamophobia” is now widely used to describe various forms of anti-Muslim hostility, but its scope remains an issue of intense debate. While some argue that the term is necessary to combat rising hostility toward Muslims, others caution that it has been applied too broadly. At present, the term can encompass everything from hate crimes to political disagreements, creating a situation where almost any criticism of Islamic practices could potentially be deemed Islamophobic.

Books like Islamophobia by Chris Allen and Islamophobia: The Challenge of Pluralism in the 21st Century edited by John L. Esposito have delved into these issues, examining the phenomenon from various perspectives, including its ideological, political, and historical roots. However, even these texts struggle to create justify a definition, often acknowledging the vagueness that exists in how the term is applied. For example, not every rejection of a mosque-building permit is necessarily an act of anti-Muslim discrimination.

Similarly, critiques of Muslim culture, or the religion itself, should not automatically be seen as manifestations of Islamophobia. Yet, without clear boundaries, the term runs the risk of being misused to stifle debate, particularly when such discussions intersect with sensitive topics like radicalisation, terrorism, and immigration.

In this context, India’s call for a broader, more inclusive understanding of understanding and tolerance, guided by its timeless principle of Vasudeva Kutumbakam—the world is one family—has become increasingly relevant. At the United Nations in March 2024, India’s Permanent Representative, Ruchira Kamboj, made a strong case for recognising that religious phobias extend beyond the Abrahamic faiths. While the global conversation often focuses on Islamophobia, India pointed out that followers of non-Abrahamic religions, such as Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs often a target of hinduphobia having also faced significant religious intolerance, which has been largely overlooked by international bodies. Kamboj’s remarks are particularly poignant as global religious intolerance continues to rise. In countries like the UK, USA, Canada, Bangladesh Australia and Sri Lanka, attacks on Hindu temples, Sikh Gurdwaras, and Buddhist monasteries are on the rise. Yet these forms of religious phobia receive far less attention than anti-Muslim prejudice. By advocating for a more inclusive definition of religious intolerance, India is challenging the world to recognise the realities of all religious minorities, not just those from the Abrahamic faiths.

As the debate over Islamophobia continues to evolve, world faces a complex challenge: how to balance the protection of communities from hate, while preserving the right to free speech. By broadening the definition of religious phobias, India is not merely adding a voice to the debate—it is issuing a challenge to the global community to act more inclusively. If the international community is serious about combating hate and discrimination, it must not ignore any form of religious persecution, whether it targets Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, or Buddhists or others. As the UK continues to grapple with the complex intersection of Islamophobia, grooming gangs, and free speech, it must also decide if it is ready to confront all forms of religious intolerance including Hinduphobia with equal urgency.

(Author is Research Director at Centre for Integrated and Holistic Studies, New Delhi based non-partisan think-tank)